The Fine Art of Feminism. In memoriam Marcia Tucker, 1949 - 2006.

[...]

Which brings me to the work of Birgit Jürgenssen.1

I begin my discussion of certain of the Verbund artists with her, because I was entirely ignorant of her work until invited to contribute to this catalogue. The question as to why I did not know of her work is worth my (rhetorical) asking. While one can assume that Jürgenssen, a professor of art at the Vienna Academy, an active and productive artist, an intellectual and a cosmopolitan, was highly aware of all the contemporary production from the art world metropolises in Western Europe, U.K., and the Americas, the opposite was not the case. One of her works - I met a stranger (1996) was a collaboration with Lawrence Weiner, and I assume that Jürgenssen was interested in the work of other American Conceptual artists. Here too, the reverse is not the case. Such are the determining conditions of being situated either in the artistic center or periphery.2 Because Jürgenssen's work was only shown briefly and episodically outside the German-speaking world, and because the New York art world of the seventies and eighties was far less "global" than today, it is an open question as to how many other women artists await rediscovery. Because of the circumstances, my knowledge of Jürgenssen's work is based itself on photographic reproduction, although her artists' books are made to be seen in that form. mehr

Here is a work from the Verbund collection consisting of four photomat-type photographs by Jürgenssen (Ohne Titel (Selbstporträt) (ph670) , 1973/2006). They are of her, relatively straightforward, frontal, presumably taken one after one in a deliberate sequence. Her coiffure is variable; the spit curl sported in the top second picture, a flirtatious cedilla, appears in the third as well, but to different effect. Within each frame there are subtle - and not so subtle - variations. The face presented to the viewer in the first bears an alert, interested, almost amused expression, head slightly cocked in counterpoint to the elbow. To the right and adjacent to this image, however, is the same young woman, slim, attractive - perhaps a bit austere, given her somber clothing. Below and on the left, the woman in the third photo seems haggard but also grimly resolute. The rouged cheekbones, evident in all four pictures, are themselves rich in meaning; commedia dell 'arte, high fashion make-up, masquerade, kewpie-doll faces, anorexia - all have their own associations. A change of hairstyle, even a minor one, prompts a different reading of the woman, here sparked, in the fourth picture, by a feathery row of bangs (style ingénue). Four pictures, four women, four images, four stories; as with any photographic encounter the spectator interprets the nature of the "real" woman represented in the photo in relation not merely to what is "in" the picture, but to his or her own circumstances, psychology, experiences, and the context in which it is seen. But presented with the multiplicity of "portraits" where will we find the "true," the correct, the theological representation? That this is more or less the same tactic as that employed by Sherman in the film stills she began to produce in Buffalo, New York a few years later is apparent immediately. Such stagings of the artist were in fact widespread in the period, and can be seen in photographic work by Suzy Lake, Sanja Ivecović, Friedl Kubelka, Valie Export, and many others. Moreover, this interrogation of notions of feminine identity seems far more prevalent than its putative bad other; the affirmation of an essential feminine.

, 1973/2006). They are of her, relatively straightforward, frontal, presumably taken one after one in a deliberate sequence. Her coiffure is variable; the spit curl sported in the top second picture, a flirtatious cedilla, appears in the third as well, but to different effect. Within each frame there are subtle - and not so subtle - variations. The face presented to the viewer in the first bears an alert, interested, almost amused expression, head slightly cocked in counterpoint to the elbow. To the right and adjacent to this image, however, is the same young woman, slim, attractive - perhaps a bit austere, given her somber clothing. Below and on the left, the woman in the third photo seems haggard but also grimly resolute. The rouged cheekbones, evident in all four pictures, are themselves rich in meaning; commedia dell 'arte, high fashion make-up, masquerade, kewpie-doll faces, anorexia - all have their own associations. A change of hairstyle, even a minor one, prompts a different reading of the woman, here sparked, in the fourth picture, by a feathery row of bangs (style ingénue). Four pictures, four women, four images, four stories; as with any photographic encounter the spectator interprets the nature of the "real" woman represented in the photo in relation not merely to what is "in" the picture, but to his or her own circumstances, psychology, experiences, and the context in which it is seen. But presented with the multiplicity of "portraits" where will we find the "true," the correct, the theological representation? That this is more or less the same tactic as that employed by Sherman in the film stills she began to produce in Buffalo, New York a few years later is apparent immediately. Such stagings of the artist were in fact widespread in the period, and can be seen in photographic work by Suzy Lake, Sanja Ivecović, Friedl Kubelka, Valie Export, and many others. Moreover, this interrogation of notions of feminine identity seems far more prevalent than its putative bad other; the affirmation of an essential feminine.

Judith Williamson's brilliant discussion of Sherman's film still pictures of 1978-84 are no less apt a description of Jürgenssen's.3 My point here is not to argue for the precedence of Jürgenssen or to establish her as a "precursor" to Sherman, but to remark on the spontaneous appearance of certain procedures, working methods as well as shared thematics. These provide an interesting counterpoint to the current vogue for "pumped up" non-portraiture that has been so well received in the U.S. 4 In any case, a partial list of women artists who photographed themselves for their own artworks (with or without auxillary staging, costumes, or other transformatory elements) would include Eleanor Antin, Linda Benglis, Valie Export, Lynn Herschmann Leeson, Sanja Iveković, Friedl Kubelka, Suzy Lake, Ana Mendieta, Katharina Sieverding, Hannah Wilke, and Francesca Woodman and this is apart from the numbers of women artists appearing in their own films, videos and performance practices. 5

Clothes, Shoes, and Make-Up

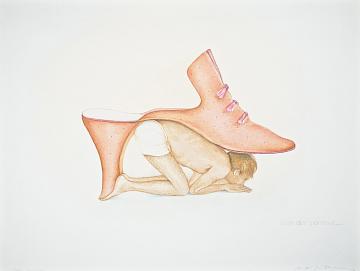

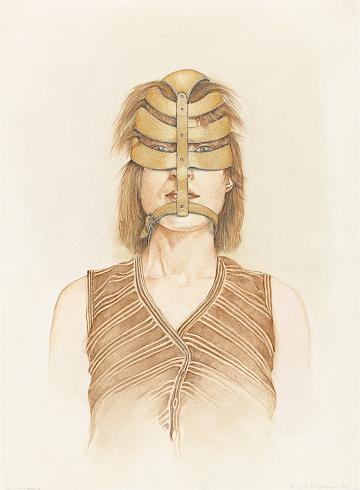

It seems that one of Jürgenssen's most well-known works exhibited in her lifetime was a chair-size chair in the form of a high heeled shoe. I have not seen this other than in a book reproduction, but fortunately, there exists a literally sensational artists' book/catalogue of Jürgenssen's Schuhwerk. 6 In this beautiful book, covered with a lipstick-red suede material, the tactile surface, like the color, announces its fetishistic appeal. In Schuhwork: Subversive Aspects of "Feminism", are found Jürgenssen's dazzling variations on the theme of the shoe. In the form of sculpture, drawing, photography, collage, and other media, Jürgenssen's shoes are made to enact the rituals of domination and subordination (see Unter dem Pantoffel(z418) , Schuhmaske(z406)

, Schuhmaske(z406) ), but are also mobilized for contestation (see Gretchen von Faust (ph1541)

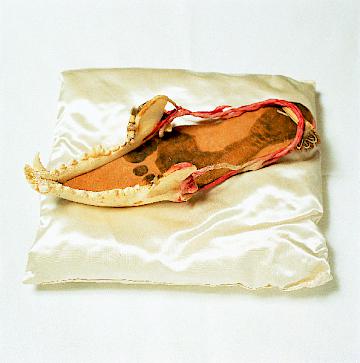

), but are also mobilized for contestation (see Gretchen von Faust (ph1541) ). As it happens, in San Diego, more or less at the same time, Martha Rosler produced a text/photo installation work using shoes entitled She Sees Herself a New Woman Every Day. And in many of Hannah Wilke's photographs of herself, she wears nothing but high heeled shoes. All of which is to indicate, that beginning with Meret Oppenheim's trussed high-heeled shoes on their platter (Ma gouvernante, 1936), women artists have recognized that there is much to be mined in footwear. But unlike the laboring shoes of Vincent, or the Pop shoes of Andy Warhol, Jürgenssen's are alternately horrific (Relikteschuh (s1)

). As it happens, in San Diego, more or less at the same time, Martha Rosler produced a text/photo installation work using shoes entitled She Sees Herself a New Woman Every Day. And in many of Hannah Wilke's photographs of herself, she wears nothing but high heeled shoes. All of which is to indicate, that beginning with Meret Oppenheim's trussed high-heeled shoes on their platter (Ma gouvernante, 1936), women artists have recognized that there is much to be mined in footwear. But unlike the laboring shoes of Vincent, or the Pop shoes of Andy Warhol, Jürgenssen's are alternately horrific (Relikteschuh (s1) , with its bloody footprint, crab claw, teeth, and sinew); uncanny and disturbing (for example, Zungenleckschuh (s16)

, with its bloody footprint, crab claw, teeth, and sinew); uncanny and disturbing (for example, Zungenleckschuh (s16) , 1974), or imaginatively bizarre (and funny), as in Netter Raubvogelschuh (s9)

, 1974), or imaginatively bizarre (and funny), as in Netter Raubvogelschuh (s9) (1974/5). Drawings that are included likewise range from the brilliantly diabolic to the nightmarish incarnations ofDominion in the Everyday (this is the title of a videotape by Martha Rosler, 1978).

(1974/5). Drawings that are included likewise range from the brilliantly diabolic to the nightmarish incarnations ofDominion in the Everyday (this is the title of a videotape by Martha Rosler, 1978).

What seems evident in Jürgenssen's work, as it is with many of her peers, is its engagement with the trivial and the debased, its tireless and inventive elaborations on the patriarchal if not misogynist imaginaire. If women have been associated with the animality, why not re-present this particular cultural fantasy with all the seriousness it deserves? (See Jürgenssen's Ohne Titel (Selbst mit Fellchen) (ph679) ,1977/78) where her face is masked with that of a [dead] fox? The foxy lady, but also lady inside fox, long a myth in Northern Europe and doubtless elsewhere. 7 If women have been thought to be captive of their own narcissism and captivated by their "own" image, why not work with mirrors, with one's self image, with one's "looks", with one's makeup, diet, and, of course, one's feminine love of clothing and fashionable display (see Cindy Sherman's pictures for Dorothée Bis). These were working methods as common in the Los Angeles Women's House as in London or Vienna. The rituals of feminine maintenance, from crucifying manicures (see Alexis Hunter, Valie Export's excruciating video) to making-up (Antin, Wilke), to marking the body with writing or image (see Valie Export's tattooed garter, Body Sign Action), 8 to the ultimate art of making-up - the work in progress that is Orlan). Such art practices based on reversals of hierarchical binaries might be characterized as the initial deconstructive move of feminist practice. So too the artwork dealing with the maintenance of daily life, including urban sanitation (see Mierle Laderman Ukeles), although again, this moves us to another medium. Clothes, shoes, make-up, manicures, all the fripperies of femininity or the material activities of women's labor are not in these works re-valorized but repositioned, re-signified. Because femininity-as-image (as ideal, mystique, refuge, object of knowledge and investigation) is itself a fetish, if not the fetish, it is chimerical, multiple in forms, hydra-or medusa-headed. Like the women in Freud's audience to whom Freud redirected his question about the enigma of femininity, "you are yourselves the problem," the woman artist working with the imagery of an always-already fetishized femininity occupies a position both inside and outside the psychosexual and cultural staging of fetishism. In this respect, it is possibly of some relevance to note that certain of those artists who most directly used themselves and their bodies to explore the imbrication of fetishism with femininity - Benglis, Jürgenssen, Mendieta, Wilke, Woodman - were all themselves quite beautiful women and thus lived their femininity in a particular way. Alternatively, certain work where the artist used herself as a model, as a physical medium as did Cindy Sherman, Eleanor Antin, and Lynne Hershman Leeson, the woman artist as individual face or body is vacated, withdrawn, and replaced by her own inventions and personae. 9 "Roberta Breitman," Leeson's alter ego, or "Eleanora Antinova," Antin's eponymous black ballerina from the Ballets Russes, are as real or unreal as femininity itself. 10 In France, Sophie Calle was independently orchestrating - directing - herself in her daily life as an artist in relation to her own invention. The speculative presence or absence of the artistic subject within either image or photograph or performance, and in work such as this, echoes the parallel question as to whether there exists an authentic and autonomous identity "behind" the representation.

,1977/78) where her face is masked with that of a [dead] fox? The foxy lady, but also lady inside fox, long a myth in Northern Europe and doubtless elsewhere. 7 If women have been thought to be captive of their own narcissism and captivated by their "own" image, why not work with mirrors, with one's self image, with one's "looks", with one's makeup, diet, and, of course, one's feminine love of clothing and fashionable display (see Cindy Sherman's pictures for Dorothée Bis). These were working methods as common in the Los Angeles Women's House as in London or Vienna. The rituals of feminine maintenance, from crucifying manicures (see Alexis Hunter, Valie Export's excruciating video) to making-up (Antin, Wilke), to marking the body with writing or image (see Valie Export's tattooed garter, Body Sign Action), 8 to the ultimate art of making-up - the work in progress that is Orlan). Such art practices based on reversals of hierarchical binaries might be characterized as the initial deconstructive move of feminist practice. So too the artwork dealing with the maintenance of daily life, including urban sanitation (see Mierle Laderman Ukeles), although again, this moves us to another medium. Clothes, shoes, make-up, manicures, all the fripperies of femininity or the material activities of women's labor are not in these works re-valorized but repositioned, re-signified. Because femininity-as-image (as ideal, mystique, refuge, object of knowledge and investigation) is itself a fetish, if not the fetish, it is chimerical, multiple in forms, hydra-or medusa-headed. Like the women in Freud's audience to whom Freud redirected his question about the enigma of femininity, "you are yourselves the problem," the woman artist working with the imagery of an always-already fetishized femininity occupies a position both inside and outside the psychosexual and cultural staging of fetishism. In this respect, it is possibly of some relevance to note that certain of those artists who most directly used themselves and their bodies to explore the imbrication of fetishism with femininity - Benglis, Jürgenssen, Mendieta, Wilke, Woodman - were all themselves quite beautiful women and thus lived their femininity in a particular way. Alternatively, certain work where the artist used herself as a model, as a physical medium as did Cindy Sherman, Eleanor Antin, and Lynne Hershman Leeson, the woman artist as individual face or body is vacated, withdrawn, and replaced by her own inventions and personae. 9 "Roberta Breitman," Leeson's alter ego, or "Eleanora Antinova," Antin's eponymous black ballerina from the Ballets Russes, are as real or unreal as femininity itself. 10 In France, Sophie Calle was independently orchestrating - directing - herself in her daily life as an artist in relation to her own invention. The speculative presence or absence of the artistic subject within either image or photograph or performance, and in work such as this, echoes the parallel question as to whether there exists an authentic and autonomous identity "behind" the representation.

In the theater of fetishism, one of the most ubiquitous props is the stiletto high-heeled shoe, although this is only one possible template from which to articulate the fetishism of feet and shoes. The three-inch lotus foot, the ideal form of the Chinese woman's bound foot, is perhaps the ne plus ultra of this formation, but the logic of the fetish is the same in both cases. 11 Doubtless this recognition is what prompted Oppenheim to make La gouvernante just as it prompted other forms in these other instances.

Exploring the fetishism of the erotic and the eroticism? of the fetish, Jürgenssen's own shoe work is as ingenious as it is unsettling. In keeping with the magical qualities of the fetish, these are embodied, incarnated, in a commodity form (the shoe as shoe). Jürgenssen's Relikteschuh (s1), resting on its white satin pillow, remind us that the ballerina's silken slipper, like the bound foot lodged in its gorgeous slipper, deny the mutilation and the wounds, and the blood that are their cost. It is thus an example of the work of artistic de-sublimation, and unveiling the fetish is therefore one of the preoccupations informing work as nominally disparate as that of Annette Messager (Mes vœux), Hannah Wilke, and Linda Benglis (Untitled, 1974, first published in Artforum); as disparate as that of Francesca Woodman and Cindy Sherman. One might go further and see even in such work as that of Doris Salcedo (Los Atabillos - the shoe reliquary work) a related preoccupation with fetishism, both as a form of longing and loss, a religiously or ritualistically invested object, an uncanny memorial to something missing or disappeared.

The shoe fits, as it were; it served these artists well as a material, it served equally well as an emblem of feminine sacrifice pain and redemption (e.g. the stories of Cinderella and Hans Christian Andersen's little mermaid). The shoe is both utilitarian and quasi-mystical, it can be appended to the Bataillean notion of basesse or elevated to aesthetic heights. It can function quite literally as the most precious and revered of objects, but it may be also highly tabooed; for example, the hand-embroidered slippers that women in China made for their lotus feet. That it was women who bound the feet of their daughters and granddaughters and that it was women too who fabricated and embroidered their own exquisite shoes is suggestive in several ways. It reminds us that patriarchy is not something imposed by outside forces but something internalized by all its subjects. The shoe may also be an icon, and that in two or three dimensions, and it can easily be, as we have seen, a sculpture. It is, as well a ready-made, an already-made, an already-made, ready-made fetish. In this respect, it is the achievement of Jürgenssen's Schuhwerk (and its accompanying drawings and graphics) to have invented yet another unimagined form, one that operates to unmask, to de-sublimate, to de-fetishize the fetish itself.

[...]

1) See also Edith Futscher´s essay "Clowning Instead of Masquerading: Birgit Jürgenssen´s Photographs of the Nineteen-Seventies," in this publication pp.106-125.

2) Irit Rogoff has many interesting things to say about the geographies of the art world. See Irit Rogoff, Terra Infirma: Geography´s Visual Culture (London, 2000)

3) When I rummage through my wardrobe in the morning I am not merely faced with a choice of what to wear. I am faced with a choice of images ...; This seems to me exactly what Cindy Sherman does in her series Untitled Film Stills photographs. To present all these surfaces at once is such a superb way of flashing the images of 'Woman' back where they belong, in the recognition of the beholder." Judith Williamson, "A Piece of Action: Images of 'Woman' in the photography of Cindy Sherman," in Cindy Sherman, ed. Johanna Burton (Cambridge, 2006), pp. 39-52, here p. 29.

4) I refer to the very large color photographic portraits by Thomas Ruff and others.

5) This division between performance work and photography, especially what might be called performative photographic practice, tends to obscure many shared themes, topics, and preoccupation between the different mediums and forms.

6) Birgit Jürgenssen, Schuhwerk. Subversive Aspects of »Feminism«, exh. cat. MAK, Vienna 2004.

7) A modernistic version of this folk tale is David Garrett, Lady into Fox (London, 1922).

8) For two excellent discussions of this work see Regis Michel, "I am a Woman/ Je suis une femme," in VALIE EXPORT, exh. cat. Sammlung ESSL Kunst der Gegenwart, Klosterneuburg/Vienna (Vienna 2005) and Mechthild Fend, "Zeichen in der Oberfläche: VALIE EXPORTS Body Sign Action," Psychoanalyse im Widerspruch, vol 15, no. 29 (2003), pp. 51-59. See also the exhibition catalogue VALIE EXPORT: Mediale Anagramme, Neuer Berliner Kunstverein (Berlin, 2003).

9) This is a central issue in performance work where the "presence" of the artist as individual subject and the "role" the artist in her performance are entwined but not reducible to one another. In other works is it the individual artist Yoko Ono who submits to having her clothing cut off her body in Cut Piece or does she become in the performance The Performer who stages the work of the Artist? For an excellent discussion of the complexity of subject position in performance practice see Rebecca Schneider, The Explicit Body in Performance (London and New York, 1997).

10) Antin´s impersonation, if that is the correct word, of a woman of color who is also a ballerina who is also an expatriate is one of the few works I am aware of besides Cindy Sherman in her Bus Riders series to have dare to work in "black face". It was artists of color, for example Adrian Piper, Howardina Pindell, and Bettye Saar who directly engaged with race in their art. In the U.S., it was at least another ten year than in Europe for artist of color to be truly "visible" and many of the women of color who become prominent in the nineteen-eighties (i.e. Carrie Mae Weems, Lorna Simpson, Renée Cox, Renée Green, Lorraine O'Grady etc.) would be considered "second-generation" artists.

11) A brilliant discussion of Chinese foot binding is Wang Ping, Aching for Beauty. Footbinding in China, Minneapolis 2000.