November 8 – December 21, 2024

‘There is no place like home’, it says succinctly (alluding to the still ideally intact world of the home in The Wizard of Oz) in David Lynch's TV series Twin Peaks (1990/91), in which the American small-town idyll gradually turns out to be a nightmare of abysmal dark-sexual fantasies turns out to be a nightmare of dark, sexual fantasies and breaks down at its innermost core - the family home.

Locating the uncanny precisely where it is least suspected at first - namely within one's own four walls - is suggested by the etymological origin of the term: Thus the word ‘heimlich’ not only stands for homely, cosy, belonging to the home, not strange or familiar, but also for hidden, kept hidden or secret, which leads Freud to the conclusion ‘that the little word heimlich also shows, among the multiple nuances of its meaning, one in which it coincides with its opposite unheimlich ... So heimlich is a word that develops its meaning according to an ambivalence ... Unheimlich is somehow a kind of heimlich. ’

Through this semantic subversion, categories thought to be stable suddenly turn into their opposite - ‘heimlich’, which conjures up ideas of an area protected from the outside world, in which the unknown is banished from the door, merges seamlessly into the opposite sense of threatening strangeness inherent in ‘unheimlich’. The home becomes the place where the modern subject finds itself, forms its subjectivity, but also encounters its abyss, the familiar, which suddenly appears strange, and the other, which returns not from outside, but as something repressed from within. The interior is the place where the subject experiences ‘not being master of one's own house’, as Birgit Jürgenssen states in reference to Freud's famous formula. mehr

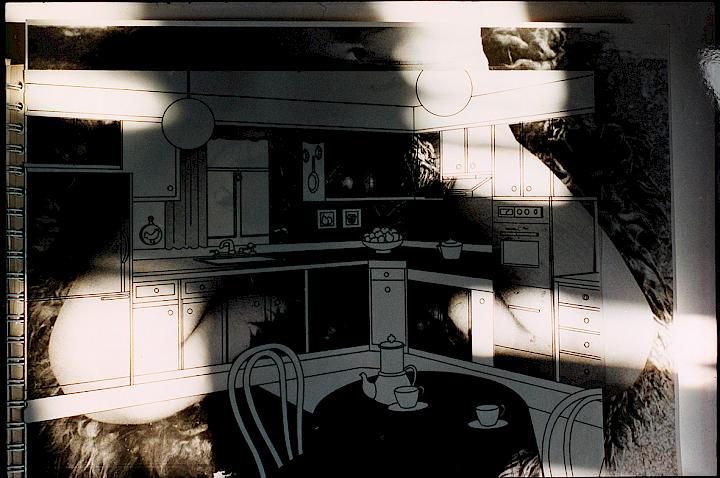

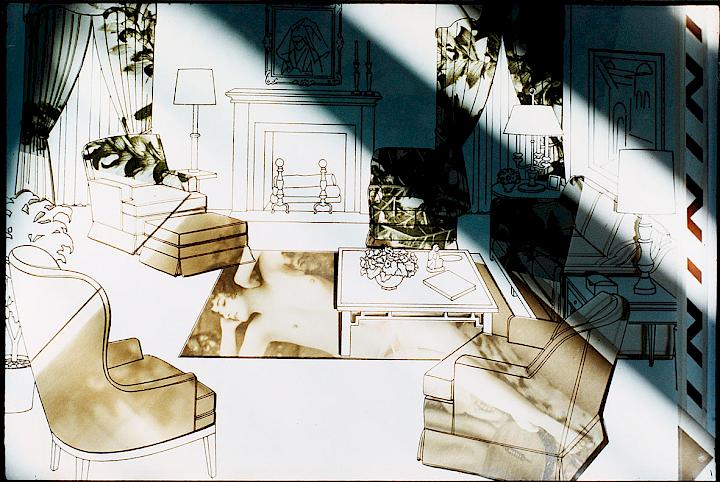

With her extensive photo series of interiors, which she created between 1996 and 1998, Jürgenssen takes up the topos of the home and the associated ambivalence of strange/familiar, secret/uncanny as well as inside/outside, private/public. Her source material is an interior design manual from 1976 - The Instant Decorator - which represents the bourgeois middle class's generalised ideal of ‘beautiful living’. It represents the middle-class middle class's generalised ideal of ‘beautiful living’ and, with the kitchen, living room, bedroom, bathroom and children's room, contains all the interior spaces along which the middle-class household is typically structured. The ensembles, reminiscent of the advertising aesthetics of the 1960s, which pop artist Roy Lichtenstein used as the basis for his interiors, are printed on transparent foils that invite the reader to design his or her own home ‘individually’ by testing out different colour patterns, for example, according to the motto ‘beautify your home’, as Jürgenssen notes in her notebook. This kind of haunted individualism can obviously manifest itself less in standardised interior design, but remains limited to the differentiation of decorative surfaces. In her photo series, the artist alienates the templates by underlaying the transparent surfaces with found image material that irritates the sterile domestic backdrop and in this way confronts different levels of reality and time, which she then photographs and develops several times with the addition of content - for example through further layers of surface forms, drawings or light and shadow reflections.

„Wie erfährt man sich im Anderen, das Andere in sich?“. Aspekte des (Un)Heimlichen im Werk von Birgit Jürgenssen

by Heike Eipeldauer

Excerpt from: Ausst. Kat. Bank Austria Kunstforum, 2010/11, S. 35–36.