Birgit Jürgenssen. McCAFFREY FINE ART

Austrian-born feminist artist Birgit Jürgenssen produced a wide variety of work – paintings, photographs, performances, sculptures, collages, drawings, and clothing, among other form and media – before her untimely death in 2003 at age fifty-four. Inspired by the writings of Sigmund Freud, her oeuvre features classically Surrealistic juxtapositions that allude to the associative operations of the unconscious, and often seems abuzz with psychosexual energy. Her work marries this interest in Freudian psychoanalysis to a political optimism – “between ‘waking and dreaming’ we can learn ‘seeing,’ and recognize ‘a tomorrow’ in the future,” she once wrote. This outlook manifested in a focus on uprooting sexism, a position that evolved partly in reaction to the milieu in her homeland when she attended art school in the 1960s, a decade marked by (mostly male) Viennese Actionism. mehr

A recent, enlightening exhibition – her first solo show in New York since 1997 – presented thirty of Jürgenssen’s pieces. It served as an overdue corrective, but moreover shed significant light onto an aspect of her practice – works on paper – that has not been embraced as much as her photography has. A small anteroom to the main gallery featured four pieces that focused on Jürgenssen’s preoccupation with animal pelts and anthropomorphism (a utopic take on human-animal hybrids is one theme of Jürgenssen’s work). These included Ohne Titel (Selbst mit Fellchen) (ph679) (Untitled [Self with Little Fur]), 1974/2011, one of three photographs in this show, and Untitled (z225)

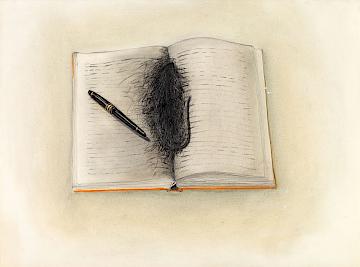

(Untitled [Self with Little Fur]), 1974/2011, one of three photographs in this show, and Untitled (z225) , 1980, a drawing depicting a diary-size book spread open to what appears to be a vagina or small animal emerging from the book’s hinge. A pen on the book points to a wispy, tail-like line, leading to the adjacent Ohne Titel (2 Mäuse) (z901)

, 1980, a drawing depicting a diary-size book spread open to what appears to be a vagina or small animal emerging from the book’s hinge. A pen on the book points to a wispy, tail-like line, leading to the adjacent Ohne Titel (2 Mäuse) (z901) (Untitled [2 Mice]), 1979, in which a pair of hybrid mouse-woman creatures lie on a bed. The feminist implication of these drawings comes not simply from the imagery, but from something unsettling, unknowable, and unnamable, the artist’s with to leave the viewer befuddled.

(Untitled [2 Mice]), 1979, in which a pair of hybrid mouse-woman creatures lie on a bed. The feminist implication of these drawings comes not simply from the imagery, but from something unsettling, unknowable, and unnamable, the artist’s with to leave the viewer befuddled.

Turning the corner into the larger space, one encountered several finely rendered drawings: Die geschwungene Linie ihrer Augenbrauen (z200) (The Curved Line of Her Eyebrow), 1977, which portrays a cropped view of a brow with oversize hairs as thick as branches; Adern-Grenzlinien im Körper (z199)

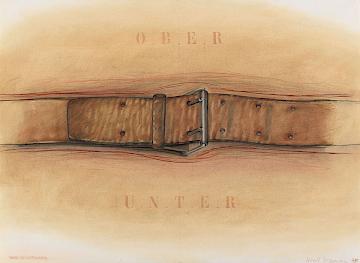

(The Curved Line of Her Eyebrow), 1977, which portrays a cropped view of a brow with oversize hairs as thick as branches; Adern-Grenzlinien im Körper (z199) (Veins-Borderlines in the Body), 1978, wherein small white sailboats glide down blue tributaries snaking through flesh; and Ober Unter der Gürtellinie (z194)

(Veins-Borderlines in the Body), 1978, wherein small white sailboats glide down blue tributaries snaking through flesh; and Ober Unter der Gürtellinie (z194) (Above Under the Belt Line), 1978. In the last, a belt merges with skin, creating an uncanny effect that rhymed with another work, Froschschultergürtel (Ergänzung zum menschlichen Bewegbungsapparat) (z719)

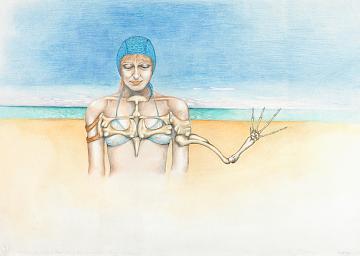

(Above Under the Belt Line), 1978. In the last, a belt merges with skin, creating an uncanny effect that rhymed with another work, Froschschultergürtel (Ergänzung zum menschlichen Bewegbungsapparat) (z719) (Frog Shoulder Belt [Addition to Human Motion Apparatus], 1974, which depicts a swimsuited woman outfitted with a prosthetic – the chest skeleton of a human-size frog as well as one of its arms. While the woman’s actual arms hang down at her sides, suggesting bondage, there is also a potential for liberation: She looks ready to dive into the green sea behind her.

(Frog Shoulder Belt [Addition to Human Motion Apparatus], 1974, which depicts a swimsuited woman outfitted with a prosthetic – the chest skeleton of a human-size frog as well as one of its arms. While the woman’s actual arms hang down at her sides, suggesting bondage, there is also a potential for liberation: She looks ready to dive into the green sea behind her.

The show resonated with ideas that refuse to be labeled or pinned down. One’s desire to find affinities in her work that would underwrite comparisons with fellow Viennese artists Maria Lassnig and VALIE EXPORT, or with other forebears in a larger constellation – from Meret Oppenheim and Claude Cahun to Eva Hesse, Yayoi Kusama, Alina Szapocznikow, and Louise Bourgeois – therefore felt forced, and at this stage also unnecessary. The surreal and Pop femininity or feminism embodied in Jürgenssen’s output is dissimilar from that of Lassnig and EXPORT, asking different questions about becoming, identity, and selfhood. For now, Jürgenssen deserves and demands more rigorous study and exhibition. The show revealed the various ways in which her singular work refuses to neatly fit within any one movement, time period, or category. My own consciousness was raised here as I observed Jürgenssen’s expansive take on feminism: one that embraces Surrealism, Freudian psychoanalysis, and utopia – and one that, like her work, also rejects a single definition.