Body I Am. Alison Jacques Gallery

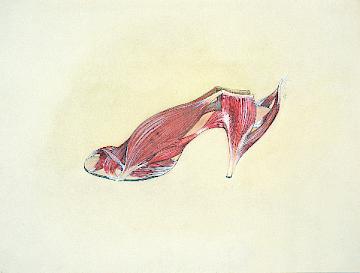

This show of three early feminist pioneers - Birgit Jurgenssen, Ana Mendieta and Hannah Wilke - is a scanty but tasty hors d'oeuvre to a much-awaited feast that has yet to be curated. Celebrated in a welcome monograph in 2009, now sadly out of print, the work of Jurgenssen (1949-2003) is also currently being revived in a solo show in her native Vienna. Represented here by two drawings, three Polaroids, two sculptures and a wall installation, Jurgenssen was also known for performances and collage. Part of the feminist Avant Garde in Austria that included the more infamous Valie Export, Jurgenssen's wit, intelligence and surrealism cleverly disrupted gender and sexual stereotypes. The cost of this is captured by her pencil drawing Backbone Alteration (z147) , 1974, in which the spine of a female torso has been prised apart as if the strength needed to exist in a female body wildly distorts its frame and central support. Her Muscle Shoe (z476)

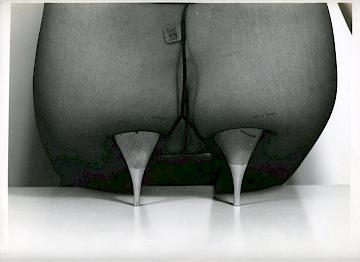

, 1974, in which the spine of a female torso has been prised apart as if the strength needed to exist in a female body wildly distorts its frame and central support. Her Muscle Shoe (z476) , 1976, shows the ruckly sinew of a skinned foot drawn as a high-heeled shoe, implying that the hideous morphing of the female foot to western erotic standards causes lasting deformity: this hybrid raw form would be impossible to function in. Other works, not shown here, however, convey the lively humour Jürgenssen brings to her theme: in Balloon Shoe (ph1658)

, 1976, shows the ruckly sinew of a skinned foot drawn as a high-heeled shoe, implying that the hideous morphing of the female foot to western erotic standards causes lasting deformity: this hybrid raw form would be impossible to function in. Other works, not shown here, however, convey the lively humour Jürgenssen brings to her theme: in Balloon Shoe (ph1658) , 1979, for example, a pair of stockinged buttocks rests roundly on two stumps of shoeless high heels. The show includes her Polaroid Untitled (Self With Skull) (ph143)

, 1979, for example, a pair of stockinged buttocks rests roundly on two stumps of shoeless high heels. The show includes her Polaroid Untitled (Self With Skull) (ph143) , 1979, which signals her interest in masks, costumes and animalistic symbolism. Here, what could be a goat or sheep skull is attached to the artist's face above her neck and shoulders which have been pigmented into a patterned hide. There is a spooky timelessness and placelessness to this image that allows it to resonate far beyond the narrowly defined and too-often routinely dismissed 1970s feminist 'body art'. It emits the lasting clarity of purpose of a Claude Cahun self-portrait.

, 1979, which signals her interest in masks, costumes and animalistic symbolism. Here, what could be a goat or sheep skull is attached to the artist's face above her neck and shoulders which have been pigmented into a patterned hide. There is a spooky timelessness and placelessness to this image that allows it to resonate far beyond the narrowly defined and too-often routinely dismissed 1970s feminist 'body art'. It emits the lasting clarity of purpose of a Claude Cahun self-portrait.

My heart sank when I read the title for this show, 'Body I Am', and my anti-essentialist hackles rose. It is somewhat misleading as each of these artists uses their body in very different ways and to differing ends. It is important to note that the title comes from a poem by Mendieta (1948-1985) which indicates that her use of her own body in her work was as much about constructing and commenting on a cultural and spiritual identity as defining the confines of gender and sexuality: 'Pain of Cuba/ body I am/ my orphanhood I live/ In Cuba when you die/ the earth that covers us/ speaks/ But here,/ covered by the earth whose prisoner I am/ I feel death palpitating underneath the earth.' Landscape and exile are key to Mendieta's creative process. Her earthworks were as influenced by Land Art, Conceptual Art and Performance Art as feminism, and the use of blood in may pieces has roots in Cuban voodoo and rites of death and rebirth, as well as in addressing menstruation and violence against women. Here, in a serise of six colour photographs called Untitled (Self-Portrait with Blood), 1973, Mendieta poses in macabre mug shots or morgue shots, her face smeared with fresh blood. They are undoubtedly linked to pieces such as Rape-Murder of the same year in which she reenacted the sexual killing of another student. It is always hard to look at such brutal explorations without revisiting the story of Mendieta's own violent and tragically early death and inscribing the images with prescience. In two Super-8 films, Mirage and Mirage 1, both 1974, Mendieta crouches naked in a wood, reflected in a mirror. She holds a gourd against her belly and then begins to stab it repeatedly. She then forces it apart and grabs out clumps of white feathers. The relationship of fecundity to self-destruction, of creativity to self-sacrifice is hauntingly and viscerally played out.

There are probably more formal links between Mendieta and Jürgenssen than between either artist and Wilke. In two of the pieces shown here, Wilke is in direct conversation with two male artists. In Period, 1991, made when Wilke was 51 and approaching menopause, she takes four postcards of an Ed Ruscha print which uses the word PERIOD and draws little winged seedlings and the words 'and more to come', 'and me to grow'. Linking the word 'period' more explicitly with menstruation and her loss of fertility, she interjects playfully and poignantly into the male canon. In What Does this Represent, 1978, one of the most confrontational pieces in the show, Wilke reworks Ad Reinhardt's cartoon of the same title of 1945 in which he drew a man pointing to an abstract painting and jeering, "What does this represent?" Below, the painting is redrawn as an angry face asking the man, "What do you represent?" This photograph shows Wilke seated naked (apart from a pair of white high heels) on a gallery floor, amid an array of toy guns and Mickey Mouse figures, holding a whistle in her hand. The text reads 'What does this represent/ What do you represent'. Wilke's face is glum, resigned. Her vagina is centrally placed, with one plastic gun directed at it.

The battlefield of art and gender is sharply staged and still needs to be staged over 30 years later, as galleries and museums abandon gender parity and young male artists recycle feminist tropes without giving any credit where it is due or reiterate violent misogyny without any attempt to deconstruct it.

In another more subdued vein, Wilke's terracotta pussy sculptures (all untitled and from the 1970s) dance delightfully between sexual explicitness and abstract formalism. Some are neat as putty-pink purses, while others make roomy yellow handbags. The female sexual object is powerfully embodied as the erotic, or possibly quite everyday, subject.

While there are many mre thematic links among these artists than could possibly appear in such a small show, it does provide a cogent appeal for a more thorough and expansive survey of this significant work.