The search for a female identity

There are many layers to the highly ironic oeuvre of Austrian artist Birgit Jürgenssen, who, throughout her life, investigated women's roles. (ph16)

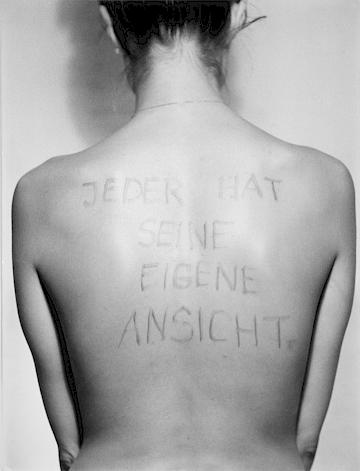

On Birgit Jürgenssen’s back the words come together to form the kind of catchy, ambiguous sentence that is all too typical of this Austrian artist’s oeuvre: Everybody has both their own way of looking at things and their own way of looking. And even these do not just arise of their own volition, not without outside intervention of any kind.

We are by definition people who can think for themselves – and this is at the heart not only of her 1975 photograph but also of the way that, as an artist, she spent her entire life questioning things, over and over again. Yet nevertheless, society and our education always play a major part in shaping the way we think, we are and we look. As part of the feminist art movement, with her multimedia oeuvre, Jürgenssen grappled with this conundrum. Similarly to Cindy Sherman, a kindred spirit of hers, (albeit someone who became disproportionately famous with work in a similar vein) particularly in her photographic oeuvre Jürgenssen is usually both artist and model, both active and passive. mehr

Female stereotypes

From the very outset, Jürgenssen (born in Vienna in 1949, the second child in a doctor’s family) worked in different media. Subtle, because it is multi-layered and ironic, her extensive oeuvre is fascinating, including, as it does, not only photography, but also drawings, sculptures, objects made of different materials, collages, watercolors, work on canvas and prints. However, more than anything else, it is with her photographs that Jürgenssen made her most enduring artistic statements, statements that have remained relevant beyond her own death in 2003.

In her photographs, by assuming roles and disguising herself Jürgenssen exaggerated female stereotypes to such an extent that these spontaneously reveal themselves as just that. The housewife, the woman as a wife and mother or, reduced to a thing of beauty and/or her physical attributes – all these are constructs created by a society with which Jürgenssen and other artists who formed part of the movement known as the feminist avant-garde took issue in the mood prevalent in Germany in 1968: by aligning themselves with the subsequent women’s movement.

The boundaries of social perception

The feminist avant-garde appropriated such roles and deconstructed them, commenting on them in a mood that ranged from humorous to ironic, until the most important thing that remained was the question of identity formation. And for all their differences, the main thing shared by all these artists is the way that they have investigated human identity, principally female identity. They explored the boundaries of social perception and patterns of thought in order to discover how firmly anchored cultural constructs actually are in everybody’s minds – for example, to what extent do shapes and stereotypes associated with women need to be abstracted until they are no longer recognizable as such?

Works such as “Ohne Titel (Selbst mit Fellchen)” dating from 1974, for example, focus on the correlation between women and animals as evidenced both in art and in myths; later work such as the series “Zebra” and Jürgenssen’s color photographs in a concave mirror (“Ohne Titel”, 1979-80) deconstruct identity to an even greater extent, dissipate it, even. The fact that for centuries now woman has been an object of projection for society’s imagination is particularly evident in her “Körperprojektionen”, dating from 1987 and 1988. Both these photographs of body projections and the distorted images, shadow images and bathtub images increasingly go beyond the representational, starting to function as a stimulus for the imagination in the true sense of the word.

“Ich möchte hier raus!” – Let me out of here!

Then, in other works, Jürgenssen explicitly highlights the perception of women anchored in society, or rather that of their bodies as a surface and object of projection in everyday life, when she literally creates roles – broaching, in her work, not only the subject of clothes, shoes, makeup, manicure, all that women’s frippery, but also that of the material manifestations of women’s work. However, this does not mean that the latter are accorded a higher status but that they are placed in a new context and reinterpreted. Jürgenssen becomes a diva, an angel, a housewife – only, after assuming these roles, to demand their liquidation. The title of one of her most famous works dating from 1976 speaks for itself – “Ich möchte hier raus!” (Let me out of here!)

“Woman is so often the subject of art but only seldom and reluctantly is she allowed to speak for herself or to produce her own pictures. Just for once I would like the opportunity to compare myself not only with my male colleagues but also with my female ones,” wrote Jürgenssen in a letter to the DuMont-Verlag in 1974, voicing a request for an anthology of female artists. The publishing company turned down her request. As it did a second one. All the more reason for Jürgenssen and other female artists of her day, both Austrians and international ones, to make use of art to create a platform for their concerns.